We are together on grandma’s sofa, me as a four-year-old, entrusted with holding in my arms cousin Kathy, a newborn whom I look upon with tenderness and awe. In a card to Kathy earlier this year, I recall that special moment and write that, in my heart, I still am holding her in my arms with prayers for recovery. This blog post is dedicated to the memory of my late cousin Kathy, her life cut short this summer by a rare type of cancer, the causes still a mystery.

We are together on grandma’s sofa, me as a four-year-old, entrusted with holding in my arms cousin Kathy, a newborn whom I look upon with tenderness and awe. In a card to Kathy earlier this year, I recall that special moment and write that, in my heart, I still am holding her in my arms with prayers for recovery. This blog post is dedicated to the memory of my late cousin Kathy, her life cut short this summer by a rare type of cancer, the causes still a mystery.

How many thousands of individuals continue to have their lives cut short by cancers, the causes unknown? And who are the scientists doing the research to find the answers and, more importantly, pursuing this work in the public, not corporate, interest?

According to American biologist Sandra Steingraber, in North America each year the statistics of cancer deaths now total more than 600,000. That number is each year, a number that she compares with the total losses of U.S. soldiers estimated at 400,000 in WWII, commemorated by a Washington monument, a wall embedded with stars.

Steingraber, in the award-winning film Living Downstream, stands in front of this wall, pointing out how a larger wall would need to be created – every year – if the deaths of cancer victims similarly were acknowledged. For, all of our lives are implicitly engaged in the war against cancer – whether we see ourselves as passive bystanders or pro-active community members who challenge this reality – simply by being alive on this earth today.

This film – based on Steingraber’s book Living Downstream – raises further questions: Why isn’t more effort being invested into full disclosures about the synthetic chemical contaminants ubiquitous in our daily lives, in the air, the water, soil and food supply – and inevitably in our bodies – and where is the political will to ban production of such poisons?

Why isn’t more effort being invested into full disclosures about the synthetic chemical contaminants ubiquitous in our daily lives, in the air, the water, soil and food supply – and inevitably in our bodies – and where is the political will to ban production of such poisons?

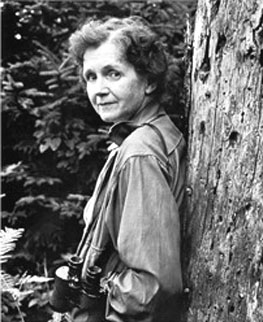

These are just two among the awkward questions to which Sandra Steingraber has dedicated her life’s work, as a biologist, ecologist, cancer survivor, author and as an internationally recognized expert on environmental links to cancer and reproductive health. She wears the mantle, bequeathed by others, as this generation’s Rachel Carson.

What is so impressive about Steingraber, and renders this film so compelling to watch, however, is not just her grace and modesty, yet also a no nonsense clarity of mind and composure in declaring her personal truth and her quest. It is a truth irretrievably woven into the fabric of her quest, to fight against the production and uses of chemicals that are killing us, as well as poisoning the life support system of this planet.

The film Living Downstream illuminates the yin-yang of Steingraber’s personal and professional life, here showing scenes with her family and a cytology check up by her urologist, and there highlighting excerpts from various keynote addresses. In on-camera interviews through which Canadian director/producer Chanda Chevannes follows Steingraber’s peripatetic travels to other places, we follow the life of a woman not only physically on the move yet, moreover, whose scientific mind continues to seek answers. Like Rachel Carson, whom I profiled in the previous post, Steingraber does not suffer fools gladly – ever.

Steingraber has the deepest respect for Carson’s advocacy in an era when the notion was forbidden, in regard to any scientist, male or female, speaking publicly about personal issues. Poignant is the wrenching reality of Carson’s final stages of terminal cancer while at the same time being invited to speak at the U.S. Congress about the findings in her controversial book Silent Spring, mere months before her death. The “C” word was anathema even to Carson’s doctors in identifying her dilemma.

Regardless, in a few scenes intermittently inserted in Living Downstream, we witness Carson’s poise and scientific professionalism. We see her matter-of-factly telling the U.S. Congress: “First, I hope this committee will give serious consideration to a much neglected problem, that of the right of the citizen to be secure in his own home against the intrusion of poisons applied by other persons…I strongly feel that this is, or should be, one of the basic human rights.”

Indeed, Steingraber sees her own life’s work as nothing less than supporting an environmental human rights movement, for which the seeds already have been sown. She advocates that folks everywhere become environmental detectives in their own communities, and demand that the well-being of our children’s lives no longer be compromised by the continuing use of synthetic chemical contaminants around us. She declares:

“If we cannot talk about these things, how can we begin to take action…It’s time to break the silence about what’s going on. We need a conversation, and an honest one, about what is happening. That’s finding ways to prevent cancer, not just racing for its cure, as an imperative need.”

The reason is, in doing a bit of detective work you might find yourselves as shocked as I am, simply in googling the current status of the chemical “atrazine.” Before I tell you my findings, my choice of looking up atrazine, a weed killer – used extensively in agriculture (and on some tree farms, golf courses and in industry) – is the primary contaminant highlighted in the film. Other poisons are mentioned too, most specifically PCBs, in pointing out how many of them originate from petroleum and coal industries.

In Living Downstream, an excellent, multi-layered film, filmmaker Chanda Chevannes’ investigation also includes the research of several other scientists who, like Steingraber, explain very clearly the step-by-step biological processes how these contaminants accumulate through the food chain of the natural environment. They provide plainly intelligent reasons why atrazine ought to be banned. The European Union did ban it some years ago; but, apparently, not yet in the USA or Canada, according to my brief detective work at this time.

When I googled “atrazine,” the federal government page that comes up for Health Canada is dated 1993 – giving data from close to twenty years ago! But even then, atrazine “was therefore considered to be a Priority A chemical for potential groundwater contamination by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) and ranked highest [my italics] of 83 pesticides in the Agriculture Canada priority scheme for potential groundwater contaminants.”

The conclusions would be comical if they were not so shocking. The suggestion on this page is that municipal, and individual home, water treatment systems can reduce atrazine significantly, and “a full re-evaluation of this compound currently in progress within the Health Protection Branch of Health Canada.” But, where is it?

Environment Canada was no more reassuring. Under the Canadian Environmental Protection Act, 1999, according to its section “Persistence and Bioaccumulation Regulations,” atrazine “was determined to be inherently toxic to humans based on a classification of `Group III: Possibly carcinogenic to humans’ according to Health Canada’s Guidelines for Drinking Water Quality (Health Canada, 2005b).

A citizen could be forgiven for not having much faith that government departments are providing appropriate vigilance to study toxins dangerous to environmental and human health, given the above scenario that I cite here to illustrate a serious problem. In fact, Steingraber in Living Downstream, raises the question about how much evidence does it take before appropriate actions happen, such as banning poisons.

Reporter Tom Philpott’s article, dated April/May 2012, titled “Ban Atrazine NOW!” tells us that the (American) Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) is not beginning to re-evaluate atrazine’s regulatory status until 2013, and no timeline on how long the process would take. Philpott concludes: ” In the meantime, farmers will continue dumping 76 million pounds of it onto farmland annually, to the delight of Syngenta shareholders.”

But, it gets worse. In an article dated February 21, 2012, the title reads “Syngenta Spends Million to Deflect Evidence Against Atrazine Herbicide.” Syngenta is the primary manufacturer of atrazine. The Center for Media and Democracy has gathered more than 200 court documents in a major lawsuit against Syngenta Crop Protection, Inc. This collected evidence proves Syngenta has spent millions of dollars to pay scientists an journalists to deny and deflect the growing documentation of the human health dangers of atrazine.

Why the film Living Downstream is so important is the call by Sandra Steingraber for all of us, as planetary citizens, to inform ourselves about the truth in order to choose specific actions to challenge the intransigence of power holders in government and commerce whose interests disregard the larger good.

In the film we see her elegantly dressed to present a keynote address at the Abraham Lincoln Presidential Museum, in Illinois, to one of her more challenging audiences. Steingraber is no fool. She clearly observes and feels, viscerally, the disinterest by many people there, who include politicians, legislators, CEOs, heads of boards, the types of folks who have the financial and political clout to make life-saving changes.

The contrast is poignant when we also see her visiting her home state of Illinois again, speaking this time in a small, intimate space with local farming families. Among them, she explains clearly the toxic, cancer-causing threats to what ought to be the healthiest baby food, mother’s milk. She cares deeply for these people, and wishes a different future for them.

Steingraber’s compassionate and astute intelligence is the force that drives Living Downstream, interwoven with her unflinching honesty in having no choice but to live through the rest of her life with uncertainty. One touching scene – to which any person diagnosed with cancer can relate – delicately reveals her vulnerability and the need to be strong, when a urology test detects a problem cluster of cells.

interwoven with her unflinching honesty in having no choice but to live through the rest of her life with uncertainty. One touching scene – to which any person diagnosed with cancer can relate – delicately reveals her vulnerability and the need to be strong, when a urology test detects a problem cluster of cells.

At age 20 she had been diagnosed with bladder cancer, and has no doubt that its origins were in the industrial environmental of her home town, Pekin, Illinois. Ten years into her profession as a biologist, she learned about “a vast accumulation of knowledge” connecting certain textile dyes with bladder cancer yet “little done to phase these chemicals out of commerce.” At that awakening in 1993, she left her tenure track job as a biologist, in order to research and produce scientific evidence for the public.

In several of my blog posts, I identify “a split in consciousness” in Western culture as being at the root of so many of our societal and environmental problems, a fact that once again plays out here. The imperative of our time is to mend our disconnected patterns of thinking, which starts with reconnecting the dots in our understanding about the web of life.

For example, each contaminant examined by health and environmental government departments appear to be examined singly, instead of what ought to be obvious, applying a recognition of the web of interrelationships between so many contaminants in our daily lives, hence the multiplied probabilities for cancers. As Steingraber says in the film:

“Each study is like a jigsaw puzzle piece, even though all by themselves you usually do not have absolute proof in the case of any one study. But, when you begin to assemble the pieces, all the arrows point in the same direction.”

Backstage at a Bioneers conference, she expresses delight in being approached by a woman from her home town. Steingraber, in response to the woman’s question about what to do, says that she never tells people what to do. Instead, she believes: “You have to bring your own passions and interests, and marry you environmental health concern with whatever it is you want to do.”

Two outstanding guides that accompany the DVD package for Living Downstream have been created, respectively, for community groups and school curricula. They embrace a range of thematic approaches for screenings and follow up discussions, written in the spirit of Steingraber’s belief that people can be motivated to choose actions from the starting point of their particular realities, whether rural or urban.

These guides offer step-by-step information from how to hold a screening, conduct a follow up discussion, facilitate workshops, and/or organize a campaign, based on various themes. Included as well are: a glossary of terms, handouts of clearly written background materials, and further recommended resources for citizens and students. Go to Living Downstream‘s website to learn more, and to order the DVD.

Sandra Steingraber’s quest, to fight the environmental causes of cancer, continues. Go to Steingraber’s website to find information about her books and related activities.

May we continue to be blessed with her gracious and intelligent presence in this world for many years to come.