“To be equal, this is what I like.” Norval Morrisseau

These simple words speak volumes, in Norval Morrisseau’s closing statement to CBC-TV’s Close Up reporter June Callwood, on the occasion of Morrisseau’s 1962 first art exhibition, at age 31. His remark followed upon Callwood’s acknowledgment that his 35 paintings had earned him $4,000, and how did he feel about it. Morrisseau, introduced as shy and mystical by a male CBC-TV newscaster, had mentioned to Callwood his childhood dilemma, to negotiate a Catholic upbringing with traditional Ojibwa spiritual beliefs and, more specifically, his personal spiritual experiences during walks in the woods. The whole conversation is poignant, given Morrisseau’s trust that his deeply felt spirituality would be understood.

These simple words speak volumes, in Norval Morrisseau’s closing statement to CBC-TV’s Close Up reporter June Callwood, on the occasion of Morrisseau’s 1962 first art exhibition, at age 31. His remark followed upon Callwood’s acknowledgment that his 35 paintings had earned him $4,000, and how did he feel about it. Morrisseau, introduced as shy and mystical by a male CBC-TV newscaster, had mentioned to Callwood his childhood dilemma, to negotiate a Catholic upbringing with traditional Ojibwa spiritual beliefs and, more specifically, his personal spiritual experiences during walks in the woods. The whole conversation is poignant, given Morrisseau’s trust that his deeply felt spirituality would be understood.

Unbeknownst to Callwood, who asked simple questions with courtesy, Morrisseau’s life, henceforth, would continue to be fraught with conflict between his inner spiritual experiences vis à vis producing works of art that foregrounded sacred imagery for a Euro-western clientele who were attracted to imagery so unique, and mysterious, to them. Moreover, the lifelong struggle for Morrisseau to survive psychologically in a secular Euro-western culture predominantly based upon materialism – success valued by financial measure – would be unimaginable.

Twenty years later, in 1982, I had begun to write about Aboriginal issues, as a newly minted journalist. My motivation was grounded both in unsatisfactory B.A. university studies in which “Native peoples” were treated as historic versus my real life encounters soon afterward in 1979, in Kenora, Ontario, with living contemporary Ojibwa and Metis individuals. The revelation for me was that Native people still existed, not merely as individuals yet, more importantly, as nations, for Canadian government and citizens to deal with and recognize. Those encounters changed the direction of my life, and I began reporting on the first peoples of Canada, whom I never had learned about throughout my formal years of education. Within a decade, I became disillusioned as a journalist, awakened not only to the cultural racism in all Western institutions yet also, with dismay, even within the news media itself.

I cannot recall how many of my stories about Aboriginal achievers were rejected by mainstream media, but instead were welcomed by then-existing Native newspapers and magazines across Canada and in the United States. Canada’s federal government subsequently terminated funding to most indigenous news publications across Canada, making it impossible for small Aboriginal nations to inform their respective peoples effectively on events pertinent to their lives. To be true to the culturally restorative mandate of the `truth and reconciliation’ initiative, I advocate that the federal government ought to provide Indigenous journalism funding again, more inclusively across the country.

In those early years, only a few Aboriginal journalists worked in mainstream media. Among them, outstanding Mohawk reporters Brian Maracle and Dan David did their best to endure the undercurrent of systemic racism in various newsrooms to produce important stories. They followed upon the new wave of Native political activism that began in the 1960s.

My film Soop on Wheels relates the life of one of the earliest among those pioneers, the late (still under-recognized) Blackfoot political cartoonist Everett Soop. The larger cultural movement, initiated by artists, spread throughout North America, planting the seeds for the American Indian Movement (AIM) in the USA, while Aboriginal political organizations developed in Canada.

Fast forward to the 1990s. I was pursuing two graduate degrees back-to-back at the Ontario Studies for Education at the University of Toronto (OISE/UT). As a member of a cross-cultural Indigenous committee advocating for Aboriginal courses of study, I recall a debate that truly shocked me. A few of the Aboriginal students questioned a Morrisseau painting (hanging in a hall way) in regard to its authenticity as Aboriginal art. By then, a freelance journalist through many years and art college graduate who initially wrote about Aboriginal artists, I was well-informed about Morrisseau, and gobsmacked that his work would not be well-known to everyone. What this debate signified, however, was how profoundly younger Indigenous people had been separated from their cultural heritage, to the degree that they were oblivious to their own artistic pioneers in the Indigenous cultural revival.

For all of the above reasons – the Indigenous cultural, and personal, spiritual roots of Morrisseau’s art; the life-affirming intention by him to share with the wider world the sacred meanings in his work; the pivotal role of his Indigenous art in the early years of Indigenous cultural revival; and the obvious continuing challenges for Indigenous people to be able to recognize and take pride in the creatively-gifted expressions by their own people – I stand totally against the current non-Indigenous painter, a young woman named Amanda PL, who demonstrated the most powerful example of wrongdoing in her appropriation of the Woodland style of art initiated by Morrisseau.

Amanda PL has no business “to make it my own,” as she is quoted saying in an online CBC article, one of a series published on cultural appropriation in recent days. These images are not her own, and never can be. Their origin is too specifically recognizable as referents not only to a different culture, yet more personally to the medicine dreams (mentioned by Morrisseau to Callwood) of another human being. Her stubborn willfulness to continue, despite an art gallery cancelling her show, illustrates the failure of mainstream society to instill awareness about, and respect in, our Indigenous history and also honour what are distinctly Indigenous contributions to deepen human understanding across cultures.

Fuller human understanding embraces the yin-yang of unity in diversity. Authentic honouring of unity in diversity is to know how to distinguish what we hold in common as a human family in relation with what each human culture contributes uniquely through its own distinct expressions of universal spiritual experience and belief, and more. As an African woman states in the excellent documentary The Destruction of Memory: “Cultural heritage is the mirror of humanity.”

I would add that the highest purpose of cultural productions importantly facilitates a continuity with our past, to remind us what is valuable to retain in regard to our origins, to awaken us to what was forfeited and needs to be recovered, as well as to recall transgressions that need amending – ultimately for our consciousness to evolve and transcend the false, human-constructed `us/them’ dichotomy. We need to appreciate why we are here on earth, through the practice of our shared higher spiritual qualities. Those qualities are manifested not only in physical artifacts such as sacred structures and ceremonial items for worship yet, moreover, kept alive through all forms of storytelling.

I have deeply appreciated the clarity of communications in recent days, on CBC television and in online CBC articles, from Jesse Wente at CBC, Trevor Greyeyes as publisher of First Nations Voice, and Niigaan Sinclair as an author and acting head of Native Studies at the University of Manitoba. Please look at the video interview with Jesse Wente on CBC radio’s Metro Morning, as well as CBC The National‘s segment “Why an editorial sparked a cultural appropriation storm.” These news items eloquently cover the concerns about `cultural appropriation,’ and point out why this issue is distinct from infringing on `freedom of expression.’ Note how these Indigenous spokespeople emphasize that production of stories about Indigenous people is different from taking ownership of Indigenous voices, even though the former is not above critique as well.

Nor should any cultural production be above critique. As a disillusioned journalist, I became involved in media literacy – an international educational movement that began in Australia, spread next to the United Kingdom, followed by Canada and the USA, some European countries and, finally, some nation states on other continents. From the late 1980s, I specialized in investigating the 500-year `back story’ to stereotypes and cultural racism, related in the pattern of misrepresenting Indigenous people in Euro-western imagery. I conducted many workshops around North America at conferences for teachers, conflict resolution professionals, and fellow journalists.

In those years, through the 1980s and early 1990s, I also attended Indigenous conferences regularly – it was an exciting time – to listen and learn about the concerns voiced by a number of traditional Indigenous people who, since then, have crossed over to the spirit world. One of the constant themes, underpinning the need for cultural revival, was the profound inter-generational spiritual devastation, hence cultural destruction, from the demonizing of Indigenous spirituality and outlawing of it. Spirituality had been at the core of Indigenous life. For example, particular rituals enabled each person to be valued and to become aware of their responsibilities, in order to feel a place of belonging in the communal embrace of the community.

In fact, I would suggest that the issue of cultural appropriation is caused by the continuing lack of wider public awareness – and continuing systemic denial about – the long history of systemically-grounded racism. It is shameful that this history is not yet a mandatory part of school curriculum, no longer merely relegated to a single course in one grade level. Instead, various curriculum subjects could incorporate not simply the political, economic and religious wrongs but, importantly, also include insights about the resilient strengths of Indigenous people and their contributions, that more completely have shaped Canada’s world identity.

As a non-Indigenous person, my perspective is that the systemic loss in my own Euro-western culture of what I consider to be a fundamental spiritual truth – that all human beings are spiritual beings in physical bodies during our earthly existence – is why Euro-western culture through centuries wreaked so much destruction upon cultures different from its own. In other words, European ancestors, collectively speaking, long ago had severed our understanding of the basic reality about human interrelationship with Spirit and with Nature. Today the same destruction continues through industrial projects that undermine the planet’s life support system, such projects fed by gross consumerism reinforced by capitalism. We all are implicit, by our very human existence, in the fate of the world environmentally. Today we are called, across the human family, to strive towards a transformation of human consciousness. To me, that shift is essential to turn around the trajectory of global environmental destruction.

My above characterization of the human condition is the very big picture wrapped around the need for serious change at multiple levels. Such change, therefore, is not limited to a meaningless litany of continuing apologies from those who are privileged and power-holders across all societal sectors. Not only do Indigenous people deserve more, but so does the human family and all planetary life.

In Canada, `truth and reconciliation’ is not simply a template of policy. More importantly, it is a guide to provide a pathway for people across cultures to pursue some genuine exploration to understand where Euro-western culture and its institutions went wrong, leading to such extraordinary, inter-generational harm inflicted upon Indigenous people, the amends long overdue. Amends can begin through individual acts of respect – such as avoiding cultural appropriation – plus essential transformation at Western institutional levels.

Euro-western society sorely needs to address its own systemic flaws perpetuated in institutions that tragically exhibit mainstream culture’s fragmented consciousness – the split from Spirit and Nature. Doing so is an essential pursuit and non-Indigenous responsibility, on top of our role in cross-cultural healing, to strive together with Indigenous people (and the larger human family) to protect and restore a threatened planetary life support system. The pursuit of healing the natural environment is one type of multi-faceted, collaborative, and life-affirming action among other possibilities, along the path of reconciliation.

Returning to the issue of cultural appropriation per se, Hal Niedzviecki’s opinion piece in Write magazine that opened with his assertion, “I don’t believe in cultural appropriation,” followed by him advocating a prize for non-Indigenous writers to exploit it, exposed the depth of societal lack of awareness about Canada’s history – more painfully evident when some high profile “white” writers then agreed to contribute money to such a prize. The entire sorry farce exposes the continuing hurtful consequences caused by ignorance when well-known and respected cultural producers behave so insensitively. The reason is, their tacit agreement (whether in jest is irrelevant as a stupid excuse) – as privileged professionals – gives permission for the larger public to behave similarly.

With that said, this firestorm is only the latest in an identity politics movement that arose with a vengeance – cultural appropriation in the eye of the storm – more than 20 years ago, in universities and across Canada’s literary terrain. I got caught in the cross hairs of it, and witnessed the dark side of identity politics when it is used and abused as a tool for censorship and, worse, an ugly method to alienate the allies who are culturally respectful. Allies are essential as bridge-builders to enhance healing across cultures. Today we need a lot more cross-cultural dialogues with related community-based actions, from talking circles to public panels, in order to facilitate the essential change that is needed for genuine reconciliation to happen. In other words, all cultures need to be better aware of history through the lenses of different cultural perspectives, to build together a bridge to mutual understanding.

I recall with a wry smile Maria Campbell’s words to me, during a long afternoon conversation many years ago, part of which was an interview with her for a profile in a Native American magazine. Maria, a Metis writer, filmmaker, broadcaster, and much more, stands among the pioneering Indigenous contemporary storytellers, who spoke her truth powerfully. Today, she herself would be valued as an elder. In her no-nonsense style, she told me that when you get everyone mad, you probably are doing something right.

to me, during a long afternoon conversation many years ago, part of which was an interview with her for a profile in a Native American magazine. Maria, a Metis writer, filmmaker, broadcaster, and much more, stands among the pioneering Indigenous contemporary storytellers, who spoke her truth powerfully. Today, she herself would be valued as an elder. In her no-nonsense style, she told me that when you get everyone mad, you probably are doing something right.

Sure enough, I eventually experienced being attacked by individuals from every side, but mostly within my own culture. Seeing Jesse Wente’s emotional commentary on Metro Morning, in which he said that he hopes never again to experience the display of insulting responses to the issue of cultural appropriation, deeply resonated with me, in accordance with an incident in my life 20 years ago. I had an experience, in a `cultural studies’ course at OISE/UT, which I wished never to be repeated. After an attack that descended from intellectual to personal, I ended up bedridden for the next two days, my body in a major spasm. I swore never again would I give away my inner power to external attackers, enabling them to silence me.

The assignment given me by a professor was to analyze an essay by an Ojibwa woman, as part of my oral class presentation to challenge the discrimination against Indigenous spirituality, within the larger issue of cultural racism in my society. I began by pointing out that the Ojibwa woman, who named the fact that she had not been raised within her own culture, had “intellectualized Native spirituality” in the way that she criticized the “alleged” events during her participation in a Native ritual. In that classroom, no Indigenous student was present. However, a vocal number of the students held Marxist views, so that discussion of anything spiritual, for starters, was fuel for attack. Among the litany of insults that followed, someone said that Native people only accepted me because they were being polite. That statement, to me, was an insult to the integrity of the many Native people whom I had encountered. Before the tears silently fell, and I still had a voice, I did point out that I never yet have met a Native person too polite to express displeasure directly to any individual, privately or publicly.

I never was shy about challenging appropriation. During a visit to the Maritimes, I triggered haughty anger from a Celtic artist who worked in porcelain. He told me about his intention to start using Indigenous imagery, and I tried to explain why he ought to rethink doing so. Even based on simple economics, it always has been difficult enough for any artist to earn income. Secondly, consider the pleasure by the buyer, who purchases a work of art directly from its creator, and can receive the layered story behind its meaning. For Indigenous artists particularly, the layers reside in the fuller cultural history, with acts of cultural revival, as well as personal healing and celebration, signified in the production of genuinely meaningful artistic expressions.

Several times I have been verbally lambasted when I criticized the exploitation of Indigenous spirituality and, worse, the misrepresentation of it, in fictional works. A foremost example was in reference to the `Medicine Woman’ book series authored by Lynn Andrews, in which a “white woman” appears to be the ubiquitous heroine through exploiting Indigenous spiritual concepts and practices while, moreover, mixing them up from diverse tribal nation sources.

What Andrews exploited through the later decades of the twentieth century was the spiritual hunger felt within Western culture, most particularly in North America. Even the Austrian psychiatrist Viktor E. Frankl, a survivor of the Nazi death camps who relocated to the United States, referred to the “existential vacuum” existing here. I also recall the words of Tuscarora scholar Richard Hill, in the 1980s, who applied the label “shake-and-bake-shamans” to those individuals within Indigenous cultures who similarly exploited the spiritual quest of any and all seekers, primarily for personal financial profit.

The trajectory in the Westernized treatments of Indigenous spirituality, therefore, began in missionaries demonizing and desecrating it, followed by political outlawing of symbolic, and actual, presentations of traditional practices – together with forbidding Indigenous languages in the schools – to rampant commercial exploitation in the late twentieth century. No wonder Indigenous people get really pissed off!

When the outlawing began, threatened Indigenous cultural practices went underground to be protected. The integrity of some ceremonial practices survived and, in accordance with traditional teachings, certain ceremonies were opened to cross-cultural participation. This was done to broaden the understanding across cultures about human interconnectedness not just among each other yet, very importantly, with all planetary life. Indeed, renewing cross-cultural dialogues and actions today about our imperilled planet could be one of the most promising and productive paths for reconciliation, at many levels.

I clearly remember the profound concern about running out of time expressed among my generation of Indigenous storytellers trying to gather and preserve traditional knowledge from the elders who had lived it, before they were all gone. Moreover, they agonized over the discernment required about how to communicate cultural traditions vis à vis the need to earn a modest living in today’s world, most particularly when communicating their own spiritual knowledge across cultures. Sharing it, nevertheless, was part of the intention as well in traditional storytelling. For example, teaching basic morality in how to conduct ourselves in this world.

The latest twist, most egregious in the educational sector, is that the works of creators ought to be available to students for free. Once again, respect still is not understood within Euro-western institutions to appreciate the arts in their higher purpose. Even as `callings’ for some practitioners, in today’s world, necessarily, they also ought to be recognized as professions, in which the ability to earn a livelihood increasingly is undermined by violations of copyright. What is overlooked is the reality that serious messengers, dedicated to gathering and disseminating knowledge, want to do so through a lifelong commitment of ongoing deep research, in a professional capacity. But, in today’s reductionist, and dumbed down mainstream, cultural climate, who will be the younger generations of such committed storytellers and messengers? As well, who will demonstrate more respect for the veteran storytellers, across cultures, before we are gone?

Indeed, across cultures through the ages, the memorable artists always have been on the cutting edge, yet sadly either overlooked or controversial in their own time. In every historic era, they have illuminated, through storytelling in various arts (writing, painting, music and theatrical performance): the perennial human condition in particular places at particular moments; who we are (or assume we are) in our human diversity; what are our responsibilities; what befalls us when we abdicate moral responsibility; and what is possible, if we have the will to strive consciously towards it.

My late Blackfoot friend Everett Soop gave me strict instructions not to present him either as a victim or as a role model in his life story Soop on Wheels. Everett wanted simply to speak his truth, and be seen as a whole person even as he presented his human imperfections, with integrity and courage. One film segment shows Everett encouraging Indigenous students to speak out for their people. He believed the power of self-determination resided in the heart and mind of each individual. Everett would be so proud of today’s growing numbers of Indigenous professionals, who are using all forms of creative media to be silenced no more.

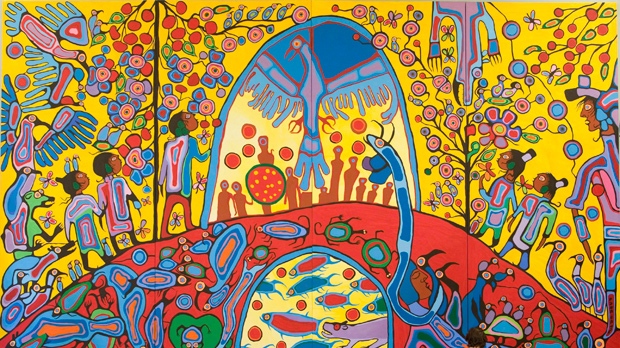

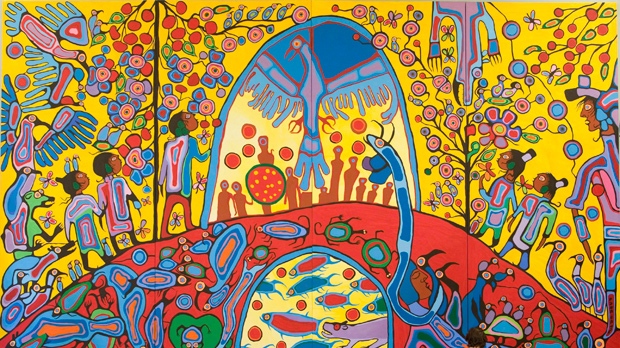

POSTSCRIPT: Morrisseau’s painting `Androgyny’ exhibited in Rideau Hall, Ottawa, and photographed in 2008 by Adrian Wyld, THE CANADIAN PRESS

Remembering Robert Redford (1936-2025), for me, is not limited to an exercise in looking back in time to the three occasions where we exchanged words but, moreover, compels me to reflect on how those encounters have continued to motivate me as a storyteller.

Remembering Robert Redford (1936-2025), for me, is not limited to an exercise in looking back in time to the three occasions where we exchanged words but, moreover, compels me to reflect on how those encounters have continued to motivate me as a storyteller.