The elm tree has a stalwart elegance, even in its leafless state, and tilting from the visible force of the wind. Behind and above the tree we can see the slate blue grey of the stormy sky. The tree is distinctive, standing tall in an open field that gloriously displays the autumn beauty of golden wheat almost flattened by the gale, the field bounded by the muted greens of roadside grass and red-leafed nannyberry bushes.

The elm tree has a stalwart elegance, even in its leafless state, and tilting from the visible force of the wind. Behind and above the tree we can see the slate blue grey of the stormy sky. The tree is distinctive, standing tall in an open field that gloriously displays the autumn beauty of golden wheat almost flattened by the gale, the field bounded by the muted greens of roadside grass and red-leafed nannyberry bushes.

The image’s creator intended the painting to be an ode to the threatened elm. For me, however, the image always has symbolized the inner strengths of grace and courage of all living beings who withstand destructive external forces.

In recently reading Silent Spring, in its 50th anniversary of first publication, I am reminded of the extraordinary grace and courage of Rachel Carson (1907-1964), deservedly heralded as kick-starting the post-World War II environmental movement. The reason is, Carson took science out of the control of industrial laboratories and government offices, and made available important knowledge to the larger public for the first time, to awaken us to the fact that environmental and human health are interwoven.

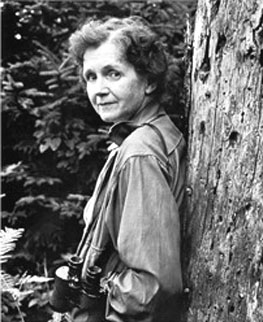

In doing so, she is a heroine in all respects, professionally and personally. When I now look upon the painted image of the lone elm in the field, vulnerable to the stormy elements, I see Carson’s apparition within the elm tree’s body. Her gaze is directed, clear-eyed, at the viewer, as in this photo of her leaning against a tree trunk, in Nature where she experienced inner peace.

When I now look upon the painted image of the lone elm in the field, vulnerable to the stormy elements, I see Carson’s apparition within the elm tree’s body. Her gaze is directed, clear-eyed, at the viewer, as in this photo of her leaning against a tree trunk, in Nature where she experienced inner peace.

This woman does not suffer fools gladly. The woman we see here has been toughened by both private and professional battles. The cause of the latter was her discovery, then exposure of, the sordid truth behind the life-threatening actions of the chemical industry and, worse, such actions rubber stamped by government. She finds the scientific and medical studies that prove, empirically, why DDT and several other chemicals, are deadly poisons.

Meticulously, for example, in Silent Spring, Carson describes how the DDT spraying to stop the spread of Dutch elm disease, killed not just the predatory bark beetle. But, moreover, the spraying poisoned the trees’ leaves, all insects who ate the leaves, the earthworms who fed on leaf litter, the soil and the robins who fed on the earthworms – in other words, DDT destroyed an entire food chain.

Similarly, Carson described how several other chemicals were just as lethal to all forms of life, from all species in Nature as well as the soil, water and air, to human life, most especially children. Indeed, children were dying and many people were being afflicted with chronic, if not terminal, illnesses. Silent Spring includes 55 pages listing her principle sources.

Carson’s diligent research to reveal these facts must not be underestimated, for she was a scientist in her own right. How she presents information demonstrates her gift to translate complex knowledge into layman’s language, in order to be accessible to the larger public.

Furthermore, the depth and breadth of Silent Spring indicates a special capability to interweave multidisciplinary investigations as well as an implicit understanding of the principles of systems thinking. Carson understood – both experientially from her own inquisitive explorations in the world of Nature since early childhood, and also empirically from her post-secondary studies in aquatic biology and zoology – that all life is interconnected.

Her understanding, however, was exceptional in Western culture, then and now – a culture that systemically is slow to shift its collective consciousness to holistic insight.

Carson had to terminate doctoral studies for two reasons, The Great Depression and her father’s death from a heart attack in 1935, to support several family members. Few jobs in science available to women, she found a job writing radio scripts about the ocean for an agency that later became the United States Fish and Wildlife Service.

At this point in her story, one wonders whether destiny was at play in the direction Carson’s life took – the path of the writer and storyteller rather than a full-time job as a scientist, where her days thereafter could have been imprisoned within laboratory walls.

That first job gave Carson access to primary science sources while, importantly, developing her gift of writing. On top of a full-time job, she also produced freelance articles for magazines up to, and following, the publication of her first book Under the Sea Wind (1941). The next book was The Sea Around Us (1951), completed a year after her first breast tumour was removed.

Her first book received several awards, and persuaded her to leave government service, regardless of being given several promotions, so that she could write full-time. The Edge of the Sea (1955) became her third book – again, each book published to acclaim.

But, life was getting more complicated. Upon her sister’s death, Carson adopted nephew Roger, while also increasingly assaulted by her very private battle against terminal cancer that cut her life short in 1964. In 1960, she had a radical mastectomy. The entire Silent Spring (1962) book project, and beyond, was beset by a number of physical setbacks.

Her heroism, therefore, is two-fold. For in pursuing her research on Silent Spring, the societal battlefield ahead became increasingly clear, although not the extent of the future guns directed to the attempted destruction of her professional integrity and personal dignity.

The guns included: shameful sexism, slandering and soulless arrogance; denial of factual scientific truth; and, of course, the ubiquitous reality of the economic power and pressure of the chemical industries. The ugly wrath that would pour down upon her after the book’s publication came from individuals in the scientific establishment hired by the chemical industry, and also economically compromised politicians.

Former Audubon biologist Roland Clement, in a 2012 interview, told journalist Eliza Griswold: “the chemical companies were willing to stop domestic use of DDT,” but only if they could strike a bargain with politicians to continue export of it to foreign countries. As for the National Audubon Society, it would not even endorse Carson’s book.

Thank goodness there always have existed more intelligent souls through history, who usually tend to be those in dissent of the status quo. They do not submit to threats from the power holders. The dissenters this time included certain esteemed scientists, such as E.O.Wilson, The New Yorker magazine which serialized Carson’s manuscript, and her book publisher Houghton Mifflin.

Furthermore, President John F. Kennedy himself, after reading Silent Spring, called for the creation of a Science Advisory Committee to do independent research and publish a pesticide report. It confirmed Carson’s findings. Since her death, various pieces of environmental legislation have grown from the inspirational, and life-affirming, soil of that courageous book.

An outstanding online exhibition now exists that maps the trajectory of the book’s influence that continues today, titled “Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring, A Book That Changed the World.” The website’s content spans a timeline from a 1963 CBS Reports television interview in Carson’s home, and the ugly attacks by industrial and agricultural interests, to the ongoing influence in education, popular culture, literature and the arts, and 2007 TV programs revisiting Carson’s legacy, seen on CBS News and Bill Moyers Journal.

The exhibition website author writes: ” Moyers intended his program to counter the libertarian-conservative attack on Carson.” Even five years later, in 2012 – fifty years following Silent Spring‘s publication – the premise of her life’s work still is debated!

The good news is, such debate gives proof that her influence has been powerful indeed. The bad news is, the fact that such a debate continues sadly illustrates that North American society still has a long way to go to appreciate the fundamental message in her writings: Humans are biological beings interconnected with all forms of life on this planet; and what befalls the earth, water, air and all other species also befalls us.

A clue about the root of the problem, as I propose below, resides in the feature article by Eliza Griswold, September 21, 2012 in The New York Times titled “How `Silent Spring’ Ignited the Environmental Movement.” For I totally challenge this statement by Griswold: “But if `Silent Spring’ can be credited with launching a movement, it also sowed the seeds of its own destruction.”

Blaming a book, a person, or a movement, for the growth of political fracturing in the USA and other nation states, and increased partisan reaction to environmentalism, overlooks the root problem that has led to a divisiveness that is not limited to the environmental movement but instead could result in the severing of societal stability.

The root problem, I suggest, is the split in human consciousness through centuries, particularly in the West. This split has led to the consequences of industrial capitalism, globalization and the commodification of life.

A growing number of planetary citizens are saying, enough. We must change how we live on this planet. The divisiveness, therefore, is between people who hold on, and try to perpetuate, an environmentally destructive economic system, and those who want to co-create new ways of interrelating, ecologically and economically, with the planet’s life support system.

Two of my earlier blog posts provide a theory behind this split in consciousness, given by the late Leonard Shlain in his book The Alphabet and the Goddess. Shlain, a heart surgeon who studied the brain, describes the two brain hemispheres, right and left, as representing respectively, the feminine and masculine principles that, together, enable fuller, balanced thinking. He also explains how and why the feminine principle has been diminished in patriarchal cultures, with an emphasis on the West.

Our collective challenge, therefore, as a human family across cultures, is the task to shift our human understanding, step-by-step, to integrate the feminine and the masculine principles and function much more in balance. This is the life journey towards our human potential, to come home to our soul, to awaken those qualities innately within each of us to become whole, and work together to heal ourselves and our imperilled planet. The possibility always is there for us to choose.

In Paul Hawken’s important book Blessed Unrest, my September blog post cites his recognition of Carson’s ground-breaking accomplishment in Silent Spring. Hawken, moreover, speaks to the global grassroots movement happening everywhere, which “sees the feminine as sacred and holy.”

Given the inevitable internal ruptures within an ever-evolving environmental movement, it is refreshing to read Paul Kingsnorth’s August 1, 2012 article in The Guardian, provocatively titled “The new environmentalism: where men must act `as gods’ to save the planet,” which he challenges, astutely. His argument is well worth reading, because it pulls us toward the essence of Carson’s message – for individuals to take responsibility to engage with natural environments as we experience them in lived reality.

Meanwhile, what speaks more about the omission of soul among Carson’s critics than about what they criticize in her is their failure to recognize her inner and outer strengths. Spiritual, emotional and intuitive resources, nurtured by direct experiences in Nature, comprised the feminine principles that carried her through daunting circumstances, including the knowledge of her own imminent death.

Yet, these feminine principles are what her critics labelled as weaknesses, while they were further ignorant of the fact that she aligned the best of the feminine with the best of the masculine, in expressing the latter through intellectual, analytical, pragmatic productivity.

Carson’s spiritual fortitude is brilliantly conveyed by screenwriter/actress Kaiulani Lee in her one-woman stage play A Sense of Wonder, performed around the United States and filmed for PBS-TV. I strongly urge you to watch Bill Moyers’ interview with Lee, and see a few excerpts from the play, on the September 21, 2007 Bill Moyers Journal episode. Carson’s soulful call for environmentalism is powerfully communicated in this play.

One poignant moment shows Lee, as Carson, reflecting on the invitation by the editor of The New Yorker to serialize Silent Spring. She recalls in a softly spoken voice how, upon hearing that news, she had put on a recording of Beethoven’s Violin Concert, and let the tears come. Her work would reach the wider public after all.

Last but not least, another website presentation of Rachel Carson’s life, generously shown by her biographer Linda Lear, at The Life and Legacy of Rachel Carson, can take you to several insightful sections. Clicking here, however, directs you first to a photographic series that begins with my favourite portrait of Rachel Carson, that exquisitely radiates the visage of her gentle soul.

May her heroism and writings continue to teach and inspire.